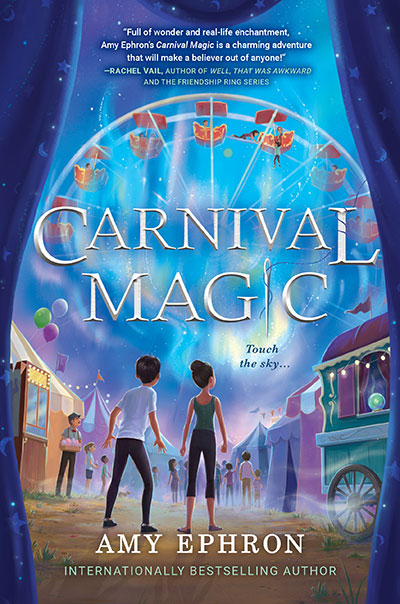

I called Amy Ephron, expecting the usual type of interview to take place, presenting one by one the questions I had carefully outlined about her newest books, “The Castle in the Mist” and its companion, “Carnival Magic,” and then jotting down her replies.

But I should have known that creative minds possess their own rhyme and rhythm, their own unexpected turns and particular mode of delivery. So, right after the initial “hello and thank you,” I was treated to a generous outpouring of stream of consciousness that practically answered my every question about the books, the prose, the characters, why she shifted to children’s books now, and a lot more. Particularly why, unlike most children’s books today, there’s an absence of violence and death in both books.

Ephron calls “The Castle in the Mist” and “Carnival Magic” a modern-day mash-up of old-fashioned children’s books, in which reality meets magic and the reader doesn’t know whether it’s real or imagined. The beauty of great writers, Ephron said, is their ability to create characters and worlds that readers are convinced exist, stories that draw in readers the same way a film can; the same way the characters in “The Secret Garden,” one of

Ephron’s favorite books, existed for her, the same way that world was as real to her as the world she lived in as a child.

The books are infused with an ethical subset, too, such as the way Tess and Max have the capacity for empathy, the capacity to take care of each other, as well as possessing a self-protective veneer. Or how they run tapes in their heads about what their parents had said to them that makes sense to use as tools when they’re on their own.

Although there’s danger, and certainly more of a proper antagonist in the second book, Ephron assured her readers that there’ll never be any explosions or any threat of violence, even though Tess and Max are being thrust into the unknown. Have they travelled through time? Has time changed? Has time collapsed? Where exactly are they?

Ephron lamented that everyone is dealing with so much these days, particularly kids. When on tour in Florida the week of Valentine’s Day, she was in Parkland at River Glades Elementary on the same campus as Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where a gunman shot and killed 17 students and staff. She was privy to students dealing with much uncertainty in this sociopolitical environment, the global political environment, and the danger in their own spaces that are supposed to be safe.

“These kids are amazing,” Ephron said, referring to kids she meets on her speaking tours in schools across the country. “We’re raising a really interesting generation of kids. Many of them have extraordinary values and a belief that they can make a difference.”

Drawing from her experiences with her siblings and her own children, who might fight with each other but, when push comes to shove, have each other’s backs, Ephron created a fearless heroine in Tess, who pinkie swears with her mathematical brother, Max. A sign to each other not to worry, a promise that they’re right here for each other, have each other’s back.

“It was really fun to create worlds where we don’t know where we are and apply the same rules to them.” — Amy Ephron

“Tess reminds me of me,” Ephron said, letting loose her throaty laughter. “There’s a kind of indomitable spirit that’s incredibly strong and, in its own way, incredibly pure, true and honest. You push us back, and we’ll come back as survivors, keep putting one foot in front of the other, keep our chin up and hope that we don’t hit our knee too hard when we fall.

“It’s really crazy!” Ephron said with a chuckle, referring to the numerous incidents that have occurred in her life that found their way into the books. “A kind of crazy magical realism,” especially with “Carnival Magic.” Although familiar with Hampshire, where “The Castle in the Mist” takes place, Ephron didn’t know South Devon, where “Carnival Magic” is set. On her way to her rented cottage in Torquay, Devon, when the driver pulled down to the side of the road, Ephron was astonished to see that a carnival had come to town and was putting up stakes.

“Meanwhile I’d already put the carnival in the story! You’re going to start laughing,” Ephron said. Over lunch, she told her friend about the traveler’s wagon in “Carnival Magic” and about the character who plays the violin, and her friend told Ephron that a man does indeed come to town every summer and parks a traveler’s wagon by the side of the road.

“And sure enough there he was!” Ephron said. The day she went to research Paignton Zoo, she learned that three endangered tiger cubs had been born in the zoo. In the meantime, she had invented the three tigers in the story.

But wait, there’s more. She learned from the taxi driver that the entire town of Paignton was once owned by Paris Singer, whose mistress was Isadora Duncan, known as the mother of modern dance. Hence, the inspiration for the aerial ballet sequences in “Carnival Magic.”

Ephron prefers readers to decide for themselves whether the incidents occurring in the books are magic or imagined. She said her intention was for Tess and Max to try to make sense of the things that happen to them in terms of the contemporary world they live in. “The hawthorn tree for me is an amazing metaphor, and I learned a great number of things about hawthorn trees that I didn’t know about when I’d written them and put them around the castle and had William say, ‘Beware of the hawthorn trees.’

“After deep research, I learned that hawthorn trees used to be thought to be a cure for a broken heart — if I only knew that when I was in my 20s, I’d have eaten hawthorn berries. Now they’re doing some research on hawthorn trees in terms of heart failure. They actually think there might be some medicinal value to hawthorn and hawthorn berries. Meanwhile the hawthorns are also thought to be, and it’s in the book, a gateway to the land of the fairies, and if you sit beside them, you might get whisked away, and if you bring the flower of the hawthorn tree inside in May, something terrible might happen to the woman of the house, which is a metaphor for the children’s mother. So the hazard of the trees for me is a metaphor for what was going on all around them.”

I brought up the mysterious character in “Carnival Magic,” who refers to a silver plane named The Flying Lady as “a symbol of an equation … that potentially proves the existence of the possibility of an alternate universe.” I asked whether Ephron, too, believes in an alternate universe that our senses might be incapable of detecting? “That was kind of a weird thing, too.” After she drew the equation on the side of the plane in “Carnival Magic,” Ephron looked it up and learned that a similar physics equation exists that may prove the existence of an alternate universe. That’s “if you believe in physics. But who knows if physics believes in physics!”

Ephron said she had once read “a bunch of books about quasars and black holes and maybe this could be some kind of sense memory of an equation that I remembered because I actually know a little bit more math than I look like I know. It’s just an odd thing about me.”

Ephron does not see her foray from writing adult books into children books as challenging or as shifting gears because a lot of what she has done, including her journalism, has been what she calls period writing. She said that no matter what period a writer is writing about, one has to find the voice and all the other accoutrements that go along with the time — the pace, the food, the slang, the clothes and the emotions. Every single piece has to fold together to create a world.

The sociopolitical backdrop is also what defines a period. “It defines the way you and I politically view the world,” she said. “It defines our actions. It defines the people we revere and want to emulate. It defines our sense of conscience, even though it’s really getting trying to have a big sense of conscience these days. So for me, in terms of being a stretch, it was more an extension of all the writing that I’ve done until then. It was really fun to create worlds where we don’t know where we are and apply the same rules to them. I’m not really someone who goes by rules, but I do know what can be jarring.

“That’s something I’ve been playing with since ‘A Cup of Tea,’ the language that captures the place you evoke. The fun for me about writing these books has been letting them tell their own story to some degree. I always find that if you don’t over outline, a character can make a right turn or left turn that you weren’t expecting.”

Ephron said that a number of adults who’d read the book had made the same observation as I had: that the books can be enjoyed at any age. She hopes that’s the case, although she made a few concessions, particularly in the first book, where the language is easy enough and understandable enough so as not to lose the third- or fourth-grader.

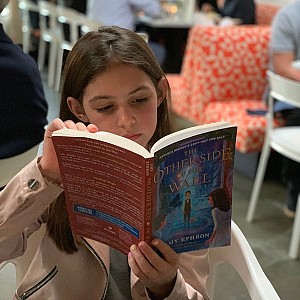

I wanted to know whether the mother of the siblings will have a stronger presence in “The Other Side of the Wall,” Ephron’s forthcoming book. After another peal of laughter, she replied that she can’t verify whether the mother is going to get there because the parents’ plane is presently delayed because of “incredibly bad weather in Europe. Their mom has somewhat recovered from her illness and decided to join the dad in Berlin because their marriage has been a little stressed by the fact that he took the job in Berlin. I’m still trying to get the mother to the other side of the wall.”

I, for one, am confident that Tess and Max, with the help of magic and their own resourcefulness, will find a way to get their mother to the other side of the wall.

READ MORE: Ephron Masterfully Weaves a World of Magic